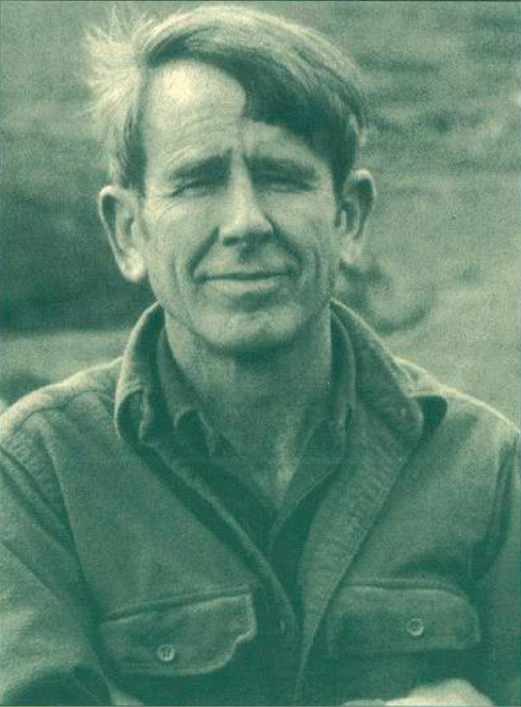

Dr. David Bruce, A California Pinot Noir Icon, Passes Away

Photo credit Jo Diaz

“One of the things about grapes is that they all have their personality.

Pinot Noir is demanding. I’ve always called it the Dune of winemaking.

You need to read Dune to understand what I am talking about.”

David Bruce

Dr. David H. Bruce, who recently celebrated six decades as a winemaker, passed away at the age of 89 years

on April 28, 2021. When his name is brought up, thoughts turn to someone that had a true passion for wine and

winemaking. Those who enjoyed drinking wine with him reveal that he was “a joy to be with.”

I met David on a few occasions, visited his winery, and wrote about him in past issues of the PinotFile. I did not

know him well personally but as I recently delved into his history I became fascinated by his life story and

accomplishments.

David was one of California’s pioneering winemakers whose combination of scientific curiosity and innovative

spirit led him to become one of the first to craft credible Pinot Noir in California. When I wrote about him in

2013 in an article titled “California Pinot Noir Doctors,” his legacy had been firmly established. I last saw him at

both the 2009 World of Pinot Noir celebration and the 2009 Pinot Noir Summit. Viticulturist Mark Greenspan,

noted in the June 2011 issue of Wine Business Monthly that he had worked with Bruce’s vineyards since 2006

and found him still active, serving as executive winemaker at his eponymous winery, and holding weekly

tastings with his staff. Greenspan remarked, “David Bruce did Pinot before Pinot was cool.”

Planting the Seed

David was born in San Francisco in 1931 to a teetotaler family that raised him in Palo Alto. He had two brothers

that died at young ages and his father, a physicist, was rarely home. His mother raised him and eventually

married Fritz Roth, one of the three founders of the Palo Alto Clinic. She ran the medical laboratory at Palo Alto

Hospital and David recalled that his mother had aspirations of becoming a doctor but raising a family took

precedent. David would remember, “I suppose I had an obligation there, or at least, I felt that way.”

David attended Palo Alto High School and split his three college years, studying pre-med at the University of

Nevada in 1949, Stanford University in 1950 (the same year as his first marriage), and UC Berkeley where he

graduated in 1951. He then entered Stanford Medical School in 1953 where he received his training at

Stanford Lane Hospital in San Francisco. After obtaining his medical degree from Stanford University in 1956,

he served his one-year internship at San Francisco County Hospital.

David’s interest in wine was sparked by a happenstance meeting of Santa Cruz Mountains vintner Dan

Wheeler while David was a student at Stanford Medical School. Dan owned a vineyard, winery, and wine cave,

crafted wines under the Wines by Wheeler label, and had a humorous logo that read, “Work is the ruin of the

drinking class.” David struck up a friendship and visited Dan at his winery where Dan introduced him to the

many varieties of wine and shared his knowledge of winemaking. This experience planted the seed.

During medical school, David began reading books about wine and one in particular, Alexis Lichine’s Wines of

France, was an important inspiration, and led to his wine epiphany. The book described the wines of

Richebourg in Burgundy as “having a noble robe.” David decided he had to get a bottle and so he did from a

retailer in San Francisco. It was a 1954 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Richebourg (a Grand Cru) that

set him back $7.50, a large sum for a bottle of wine at the time, especially for a poor medical student. David

recalled, “The minute I opened this bottle of wine, I mean, the whole room was pervaded by this floral, spicy

aroma. I remember thinking, I guess you get what you pay for. As I was drinking that wine with supper, I was

imagining myself on top of some mountain, walking through a Pinot Noir vineyard and I was simply making the

greatest Pinot Noir ever made."

After graduating with a medical degree from Stanford University, David completed a dermatology residency

from 1957 to 1960 at the University of Oregon Medical School Hospitals and Clinics in Portland. He crafted

beer on several occasions while in Oregon and in 1959 acquired some Concord grapes to make wine. The

wine was produced at his residence in an 11-gallon beer vat, pressed by hand, and fermented using bread yeast. The wine was “bad” initially, but some of it went thru malolactic fermentation and became palatable.

Looking back, David thought that if Dick Erath and David Lett had started their Willamette Valley vineyards and

winery earlier, he might have stayed in Oregon to make Pinot Noir. He realized that the Willamette Valley was

an ideal area for growing Pinot Noir.

After finishing his residency, he searched throughout California for vineyard property to grow Pinot Noir and

tasted all the Pinot Noir he could obtain. David considered the Pinot Noir wines from Martin Ray in the Santa

Cruz Mountains to be the best available at the time, and this impression combined with his familiarity with the

Santa Cruz Mountains lured him back to that region.

Making the Great Pinot Noir

In 1961, while searching for a property in the Santa Cruz Mountains, he made 200 gallons of wine in the town

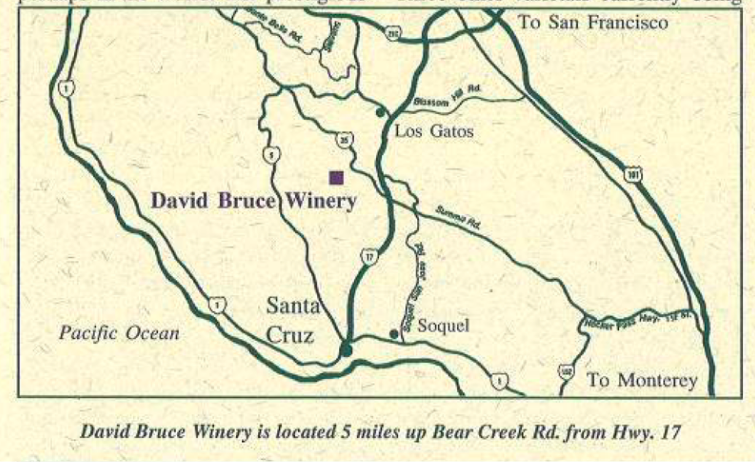

of Soquel in the Santa Cruz Mountains. He found a 40-acre property on Bear Creek Road in Los Gatos

planted to fruit and Christmas trees. It was an ideal location situated at 2,200 feet elevation with fine Hugo

loam soil that provided excellent drainage. He cleared the land and planted 25 acres of vines. Because of the

scarcity of cuttings at the time, it took 3 to 4 years to complete the planting of the estate vineyard. At the

time David developed his vineyard, there were very few vineyards in the Santa Cruz Mountains and only Martin

Ray was producing Pinot Noir in the region. David was captivated by the Pinot Noir wines of Martin Ray and

considered them better than the wines of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti.

David decided to plant the four noble grapes: Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and White Riesling. He later discovered that

Cabernet Sauvignon would not ripen, and although the site was ideal for growing White Riesling, there was no

consumer interest in that varietal. He obtained all four varieties from UC Davis Mother Plot Program that

originated from Wente’s Arroyo Seco vineyard in the Salinas Valley. The Pinot Noir-certified clonal stock

included Pommard, Martini, and Wädenswil. There is here-say that some of the cuttings came from Martin

Ray’s vines other than those that would become certified as the Mt Eden clone (37). In the early 1960s,

winegrowers were not particularly clone conscious, so Bruce would not have chosen a particular clonal type,

only specifying some “Pinot Noir cuttings.” The photo below is of the David Bruce Estate Vineyard.

David launched his dermatology practice also in 1961 and would spend the following 22 years performing two

full-time jobs (winery owner and winemaker at night and on weekends, and dermatologist during the day) until

his retirement from part-time medical practice in 1983 and full-time practice in 1985. The income from his

dermatology practice largely supported the winery financially through these years. His background in medicine

helped him succeed as a self-taught winemaker.

A winery was built on the site and was bonded in 1964. The first commercial release of David Bruce Pinot Noir

came in 1966. Bruce bought another vineyard, previously owned by the Pesenti-Locatelli family, located in the

Vine Hill subregion of the Santa Cruz Mountains in 1968. He pulled out the poorly-performing Zinfandel planted

there and replanted the vineyard to the Wente clone of Pinot Noir on its own roots. Bruce Ken Burnap, a

restaurateur from Southern California who had a passion for Burgundy, was impressed with the Pinot Noir

produced from Bruce’s vineyard. Bruce was going through a divorce and need to sell some assets in order to

buy his winery from his wife. He sold his 26-acre vineyard to Burnap in 1974, and Burnap renamed it the

Santa Cruz Mountain Vineyard, a vineyard that achieved its own cult status among Pinot Noir aficionados over

the years. Reportedly, he always regretted selling this vineyard.

The 1960s saw David concentrate on wine produced from the estate vineyard and other Santa Cruz Mountains

vineyards, The focus was on Zinfandel, but also Chardonnay, Traminer, and Grenache. The wines were crafted

in a tiny building on the vineyard property that became the tasting room in 1968 when a second larger building

was constructed to vinify the wines. Production was 2,500 to 5,000 cases annually, a sizable amount for one

person.

David’s early wines were uneven and he was to remark, “Pinot Noir is the ‘Dune’ of winemaking because so

many things can go wrong. Pinot Noir is demanding. You need to read the science fiction novel 'Dune' to

understand what I’m talking about.“ Still, he was making progress, and in 1968 began using a rotor-press and

small French oak barrels for aging.

David was continually experimenting with different wines from the beginning, and in 1964 was the first

California winemaker to produce a White Zinfandel. He discontinued this wine in 1971, saying the wine was

interesting but was something he didn’t “want to spend his life doing.” In 1969 he was one of the first to release

Blanc de Blanc and Blanc de Noir sparkling wines. He also made a Pinot Noir Blanc that he considered pleasant but discontinued

its production because he did not want to waste grapes on such an ordinary wine.

The 1970s saw the addition of the first winemaker, Steve Miller, who came in 1972. It was a decade of reaching

out and seeing what California wine grapes could do. Grape sources were expanded to eleven counties in

California extending from Mendocino County to Southern California and included Amador, the San Joaquin

Valley and even Temecula. The winery became best known for Chardonnay and his 1973 Santa Cruz

Mountains Chardonnay was one of twelve California entries to participate in the famous 1976 Judgment of

Paris. Although his Chardonnay finished last in that judging, he gained redemption in a re-enactment in 1993 at

the International Wine Exposition in Chicago where wines were submitted by the same French and American

wineries and the David Bruce 1991 Estate Chardonnay came out on top ahead of a $900 Batard Montrachet.

David produced a number of “late harvest” Chardonnays that were late picks but not particularly high in alcohol. A small amount of late harvest sweet Zinfandels were also made from 1972-1978. He lost

interest eventually in these high-alcohol, port-style Zinfandel wines and was to concentrate in the 1980s on “food wines”

that fit the definition of great wines.

A two-week trip to Burgundy was the highlight of 1977 and David initiated many winemaking techniques he learned

such as bottling from barrel, the use of different cooperages for aging, and foot crushing of the cap. These approaches would

prove key to the success of the wines of the 1980s. That trip also led him to become one of the first California

winemakers to use whole berry fermentation and whole cluster fermentation for Pinot Noir.

David had often-recited problems with cork taint in 1978 cost him $2 million in lost business according to

George Tabor writing in To Cork or Not to Cork. David reported in interviews that the loss was 7,200 cases of

wine costing him $420,000. The problem ruined his Chardonnay

reputation and market, but always the optimist, David remarked, It was a good thing in the long run for it forced

me to do something which would have been very difficult to do in any other circumstance. That is, to go to all

red wines.

The 1980s were marked by fine-tuning of the winemaking program and a better understanding of the chemistry

of Pinot Noir. With David’s attention focused on Pinot Noir, he would remark, “Any winemaker worth his salt

wants to make the great Pinot Noir.” David saw his Pinot Noir wines achieve widespread acclaim and he was

easily selling out of the 30,000 cases of wine he was producing. He had begun foot crushing of the cap in 1981

and often invited visitors to join in. That same year, he initiated whole cluster ferments and part of the 1981

vintage was 100% whole cluster fermented. David abandoned late harvest wines and concentrated on Pinot

Noir, Chardonnay, and Zinfandel wines that would drink nicely when young and also age well, or what he

considered “great” wines. The Pinot Noir and Chardonnay were sourced from the Santa Cruz Mountains and

the Zinfandel from several other wine regions.

The magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake on California’s Central Coast struck in 1989. Triggered by the San

Andreas Fault, the epicenter was in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Fortunately, no one was in the winery when the

earthquake struck leading to no injuries. The earthquake caused about $6 billion in damage and destroyed

a number of Santa Cruz Mountain vineyards.

The 1990s were notable for the destruction of the David Bruce Estate Vineyard. The blue-green

sharpshooter brought Pierce’s Disease to the vineyard and by the end of 1992, all the Pinot Noir had

been destroyed and by the end of 1993, all the Chardonnay was lost. The last Estate Pinot Noir produced from

the original vines was in 1992.

The Estate Pinot Noir program was resumed in 1996 after new plantings matured. The new plantings came

from the Chalone and Noble Hill Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains. These plantings had originally been

established with cuttings from David Bruce’s estate vineyard. Essentially, David replanted with his own vine

selection along with some mutated vines. There was a silver lining since the replanting offered the opportunity

to install better trellising. The vines at the estate vineyard had been farmed as California spread or flop, a typical

form of vine training when the vineyard was planted in the mid-1960s. David referred to it as “wild witches' hair.”

The winery became serious about Petite Sirah (the winery spelled it Petite Syrah) in the 1990s. The winery had

first made that varietal in 1970 but the vinification had been refined to reduce the tannins. It was essentially

made in the same fashion as Pinot Noir so that it was a more accessible wine. It became widely popular and

won many wine competition awards. David became involved in Petite Sirah symposiums organized by Jo Diaz

for Louis Foppiano, and he was an early member and supporter of the ‘PS I Love You’ marketing organization.

The winery took on much more debt to finance expansion throughout the 1990s. During this time, David took

on more of a managerial and emeritus winemaking position. He hired an energetic and devoted team so he

could focus on running his business. He relished having a brilliant team of four winemakers who had a special

camaraderie coupled with a talent for crafting fine wine. One of Bruce’s strengths was that he enabled people

around him to do their best with the assignments he gave them. This resulted in significant creative solutions to

production issues and led to the best wines David Bruce Winery ever made.

Winemaker Anthony (Tony) Craig began in 1991 and was joined by Ken Foster, Greg Stokes, and his wife Deborah

Elissagaray. David would leave the winemaking team alone to seek out creative solutions to problems, refine

the winemaking equipment, and upgrade vineyard management. Tony believes Bruce was having the time of his life.

He left the winemaking staff alone to their own devices but eagerly joined the winemaking staff every Thursday

morning for the weekly technical wine tasting to evaluate new wines and wines that were being considered for

bottling. Bruce never imposed his will on which wine to bottle as the wines were always tasted blind and the top-scoring wine was the one that ended up being bottled. In addition, the winemaking team would taste many

other producer’s wines for comparison. Tony told me, “It was joyous winemaking. These were the best wines

ever made at David Bruce Winery and this period in time was one of the greatest moments in my life.”

Bruce realized that by the early 1990s he was at a crossroads with the vineyard and winery. He had become

mostly known for Chardonnay, Zinfandel, Petite Syrah, and several other varietals. When Tony, who was a winemaker at David Bruce Winery for twelve and a half years, asked David

what he really wanted to be known for, he replied “Pinot Noir of course.” From that point on, the winery staff

pushed him to source and plant more Pinot Noir wherever he could. This led to a planting contract with Tondré Alarid and

his son Joe, well-known winegrowers in the Santa Lucia Highlands, and contracts with Warren Dutton of Dutton

Ranch in Sonoma County.

The winery was sourcing available Pinot Noir

from all over California, and producing large quantities of appellation-designated and vineyard-designated Pinot

Noir. Winery production expanded from 17,000 cases to 85,000 cases annually between the 1990s and early

2000s, most of which originated from Central Coast grapes. Still, the increasing popularity of Pinot Noir, driven

by a Wine Spectator feature on California Pinot Noir that included David Bruce Winery, meant there was never

enough Pinot Noir.

In the early 2000s, Jeanette, David’s spouse of 37 years, became president of the winery and assumed tight control of operations assisted by David’s sister-in-law Linda Hugger. Reportedly, David was disappointed at this juncture that his plans for expansion including opening tasting rooms in Northern California and the Central Coast never came to fruition. The entire winemaking team departed by 2003 over disagreements with management (against David’s wishes). The group included Anthony Craig who started his own label, Sonnet, and began making wine for Silver Mountain Vineyards and Tondré Wines, Ken Foster who left to become winemaker at Mahoney Vineyards, and Greg Stokes who left to make wine at Ursa Vineyards along with his winemaker spouse Deborah Elissagaray. The winemaker since 2004 has been Mitri Faravashi.

The Legacy

Those who worked with Bruce at his winery said that he was extremely well versed in the basic science of

winemaking. Michael Martella, the founding winemaker at Thomas Fogarty Winery in the Santa Cruz

Mountains was a close friend. He told me, “He had a special passion for wine and winemaking, particularly

Pinot Noir. We dined together often and he would include others who had an enthusiasm for wine. We would

walk his vineyard together and chew on skins, discussing how much whole cluster to use in the next Pinot Noir.

He was a joy to be with.”

One of Bruce’s legacies will be the David Bruce “clone” of Pinot Noir. According to John Haeger’s North

American Pinot Noir and personal communications with Haeger, the following came to light. There is no David

Bruce FPS certified clone as it represents any number of Pinot Noir selections of underdetermined clonal and

selection origins. The David Bruce clone lexicon became common parlance among winegrowers for cuttings

taken from David Bruce’s plantings in the Santa Cruz Mountains or cuttings from other vineyards planted with

David Bruce’s estate vineyard budwood. The proper term for any of these plantings should be David Bruce

selection.

For nearly 25 years, Bruce practiced dermatology while making wine at night and on weekends, eventually

devoting himself exclusively to his winery and winemaking in 1985. Because of his medical background, Bruce

was one of the first in the wine industry to extol the health virtues of drinking wine years before the 1991

appearance of the 60 Minutes television program on the French Paradox. Bruce published a booklet titled, Ten

Little Known Medical Facts About Wine That You Should Know. He was one of the first doctors to publicize that

resveratrol in red wine increased good cholesterol and reduced bad cholesterol. Bruce recommended that

hospitals have wine on patient menus and encouraged a glass of wine daily for the elderly to improve their

appetite and raise their self-esteem. He also tried to defuse the hysteria about sulfite allergies and elevated

lead levels in wine.

David is survived by four sons from his first marriage including Karli, Dana, Dale, and Barry, and several

grandchildren. Dale was the only son to show a significant interest in wine. He planted his own vineyard, made

wine, and spent two summers working for Jacques Seysses of Domaine Dujac. Still, he opted for other

careers, saying about the winery business, “Too much work and you don’t make any money.”

A memorial is planned for June 6, 2021. Details are pending.

Credits:

The David Bruce Winery: Oral history transcript: experimentation dedication and success, 2002, Regional Oral

History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley: www.archive.org/details/

davidbrucewinery00brucrich

North American Pinot Noir, John Winthrop Haeger, 2004

Michael Martella, the founding winemaker of Thomas Fogarty Winery, retired

Anthony Craig, former winemaker at David Bruce Winery, now winemaker for Sonnet, Tondré Wines, Silver

Mountain Vineyards and Gali Vineyards

Laura J. Ness, High-Performance Marketing, Wine Writing & Creative Consulting, Los Gatos, CA

The Wine Press Newsletter, Gold Medal Wine Club, Santa Barbara, CA, January 1995

Wine Business Monthly, June 2011

Official obituary prepared by David Bruce's family

Jo Diaz, Diaz Communications and PS I Love You, jo@diaz-commiunications.com