Willamette Valley, Oregon

The truth regarding the first Pinot Noir plantings in modern times in the Willamette Valley has been confusing,

with both Charles Coury and David Lett given that attribution depending on the information source. John

Winthrop Haeger told me the following. “According to Leon Adams (The Wines of America, 1978), Lett planted

his first vines in 1965, Coury his in 1966. However, David Lett told me that his first vines were planted at Eyrie

in 1966. (He did not tell me, by the way, that he had pre-planted vines at Corvallis, but that’s a plausible story.)

Other sources hold that both Coury and Lett planted in 1965. Coury and Lett came to market the same year,

and the first vintage for both was probably 1970. Certainly 1970 is the correct date for Lett, although he did not

label his first vintage of Pinot Noir as Pinot Noir, but as ‘Spring Wine.’” [My comment: many published sources

cite Coury’s first commercial releases as from the 1970 vintage, but it is unclear when he released his first

Pinot Noir for sale.] “Planting in 1965 or 1966 and harvesting a first commercial crop 4 or 5 years later sounds

pretty reasonable for the time and circumstances. I trust Adams generally, but he did not work from primary

documentary evidence. Mostly he interviewed the principals. It’s very common that dates are garbled in oral

histories - unintentionally. I’d say the only way to sort out whether Lett or Coury both planted during calendar

year 1965, or both in calendar year 1966, or one a year earlier than the other, is to compare contemporaneous

documents for both enterprises.”

Noted wine writer Leon Adams (The Wines of America, 1985 - 3rd Ed) stated, “In 1965 Lett planted the valley’s

first Vinifera vineyard to be started in five decades.”

Thomas Pinney (A History of Wine in America, 2005) credits Coury with being the first of the modern

Willamette Valley pioneers. He declared, “ Coury’s thesis concluded that the Willamette Valley would be a

place where grapes adapted to northern European regions - Burgundy and Alsace - might flourish.”

An often-quoted reference by Lisa Shara Hall, author of Wines of the Pacific Northwest (2001), states that

Charles Coury left California for Oregon in 1965 and planted “a wide range of Alsatian varieties - including

Pinot Noir,” but she does not set a specific date for Coury’s first plantings. Hall dates the Oregon Pinot Noir era

from 1965, when she says David Lett first rooted Pinot Noir cuttings near Corvallis, beginning the transplanting

of these vines to the Dundee Hills at The Eyrie Vineyard in 1966.

The Forest Grove website claims that Charles Coury purchased his 45-acre farmstead in Forest Grove at the

current site of the David Hill Winery on September 30, 1965, and “immediately began planting his vineyard in

October 1965.” (However, this is an unlikely scenario since vineyards are traditionally planted in the spring.

Most likely, he started a nursery on the site.) The website states that David Lett established his Dundee Hills

vineyard in the spring of 1966.

One piece of information that has positioned Coury in the forefront chronologically is the words of Betts Coury,

Charles’ sister-in-law, who along with Coury’s spouse, Shirley, helped Charles establish his winery. In the

book, Vineyard Memoirs, written by Kerry McDaniel Boenisch, Betts Coury quotes Charles as saying,

“Sommers is the original pioneer, not me. I was the second. Before Lett, before Fuller, and before Erath. I

graduated way ahead of those guys. Heck, they all read my thesis at Davis on cold-climate growing and

argued with me about whether it could be done successfully in Oregon. The reason I moved to Oregon in 1965

was to prove that excellent Burgundian and Alsatian wine grapes could be grown there.” It is important to point

out that Boenisch did not interview David Lett for her book, and her and Betts Coury’s accounts were mostly

taken from Charles Coury directly, or second hand, from others.

A recent interview with Dick Erath, who arrived in the Willamette Valley in 1967 and knew both Lett and Coury,

was conducted by Karl Klooster and published in the Oregon Wine Press (March 2011). Erath stated that

Coury bought Reuter’s property in Forest Grove in a foreclosure, started working on the deal in 1964 and

moved there in early 1965. (This statement is confusing since it is known Charles and Shirley Coury were in

Europe throughout 1964 and did not move to Oregon until the latter part of 1965). When asked who first

planted Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley, he said, “As far as I know, 1965 was the year and, since spring is

planting time, I’m assuming they both planted then. The difference is that David planted nursery rows (babies

to be used for propagation) and Coury put in rooted vines.” When pressed to verify the claim of Forest Grove

(and vis à vis Coury) about being the first place where Pinot Noir was planted in the Willamette Valley, Erath

begged the answer.

Perhaps the best-researched and most current information about David Lett was offered by Mark Savage, MW

(The World of Fine Wine, Issue 22, 2008) in a tribute after Lett’s passing on October 9, 2008. He notes, “In

1965, at the age of 25, by now convinced that Oregon’s Willamette Valley offered the best hope for Pinot Noir

in America, he made his move to Oregon ‘with 3,000 cuttings and a theory,’ and planted the cuttings in a rented

nursery plot while he went looking for the perfect vineyard site in which to pursue his passion.” He goes on to

say, “...in 1966 he and his new spouse Diana planted the 3,000 cuttings at The Eyrie Vineyard.” Savage

credits Lett with being “the first person to plant Vitis vinifera in the Willamette Valley.”

How to make sense out of all this conflicting information? Fortunately, David Lett’s son, Jason Lett, and David

Lett’s spouse, Diana, have chronicled David’s winegrowing career in the Willamette Valley with extensive

documentation and they agreed to share their knowledge and some of their invaluable archival material with

me. The following represents the facts based on their contributions, my research, and various reliable

reference sources including the book, The Winemakers of the Pacific Northwest (1977).

David Lett grew up on a farm in Utah, graduated from the University of Utah in 1961, and was in San Francisco

waiting to begin dental school when a road trip to Napa Valley wine country led to a life-changing epiphany. He

enrolled instead in a two year viticulture course at University of California Davis. After graduating in 1964, he

traveled to Europe, and spent almost a year visiting northern Europe, including Burgundy, talking to vintners,

winegrowers and viticulture professors about cool climate viticulture.

Charles Coury, who grew up in Oregon, obtained a degree in climatology from the University of California at

Los Angeles and was well versed in agricultural growing seasons. For a period, he sold imported European

wines for Jules Wile, then entered the University of California Davis where he was a classmate of Lett’s and

where he obtained a Masters of Science degree in Enology, graduating in June 1964. He too, would travel to

Europe after graduation, studying cool climate viticulture and clonal adaptation at INRA (National Institute for

Agronomy Research) in Alsace, France.

Both Lett and Coury found Northwestern Oregon an appealing location for growing cool climate grape varieties

despite the sentiment at Davis that Oregon was not suitable for the successful cultivation of European wine

grapes. Harold Berg, Lett’s Professor, told Lett that there were very few climates suitable for Pinot Noir in the

United States. Vintners in California had been working with Pinot Noir for years with little success and the

prevailing opinion was that it was just too hot in California for Pinot Noir. Oregon had some glimmer of

potential for both Vitis labrusca and Vitis vinifera and several research vineyards were planted in Oregon by the

late 1950s.

It has been reported in the literature that Charles Coury proposed the theory that Vitis vinifera produces the

best quality wines when ripened at the limit of its growing season. Coury considered the growing season in

Northwestern Oregon to be an opportune place to support his hypothesis and, as a result, he has been widely

credited with the idea of pursuing winegrowing and in particular, Pinot Noir cultivation, in the Willamette Valley.

However, Lett should be given equal recognition, for in his commitment to finding a cool climate to cultivate

Pinot Noir, he kept coming back to Oregon, thinking its climate and growing season was the closest to

Burgundy of any other known alternatives in the United States.

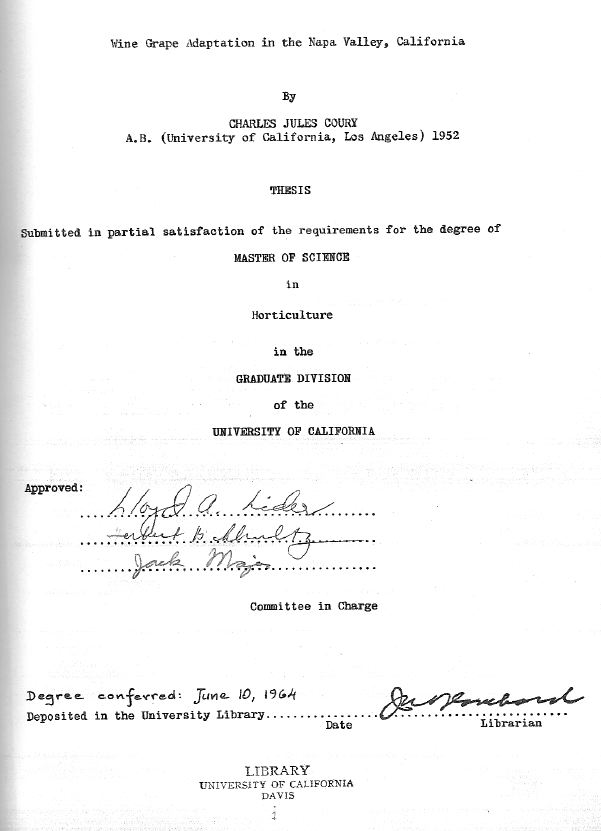

A recent review of the archives in the University of California at Davis library reveals that the only thesis that

Coury wrote and published at Davis was titled, “Wine grape adaptation in the Napa Valley, California.”

Although Coury’s thesis, published in 1964, had no reference to Oregon, Coury did delineate the relationship

between climate and suitable grape choices. He wrote, “Any variety yields its highest quality wines when

grown in such a region that the maturation of the variety coincides with the end of the growing season.” An

abstract of the thesis is available at www.wineserver.ucdavis.edu/thesis/detail.php?id27. A copy of the title

page of the thesis is included below.

The Forest Grove Economic Development Commission’s chairperson, Don Jones claims he conducted

research to indicate that Coury’s thesis “proposed that the Willamette Valley would be ideal for Pinot Noir,” and

incorrectly asserts that, “without him (Coury), our beloved wine pioneers wouldn’t have known to come to the

Willamette Valley” (NewbergGraphic.com, December 22, 2010). Jones did admit that technically, by about eight

to twelve months, Lett was the first to plant in the Willamette Valley in Corvallis, but unfortunately chose to

downplay the important distinction.

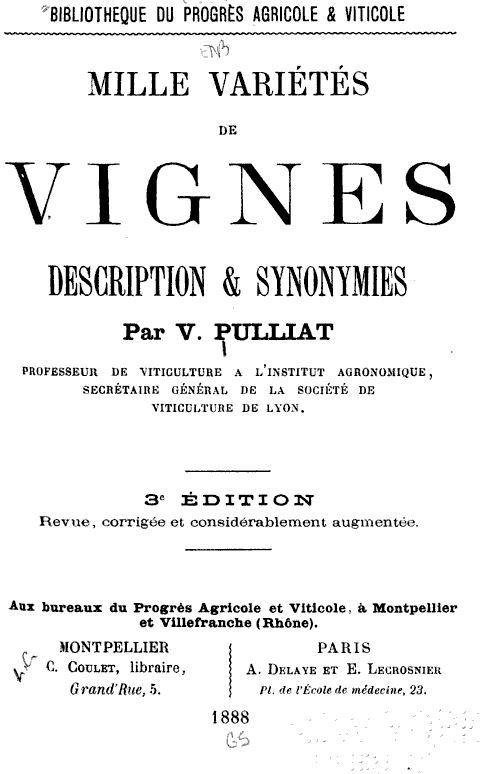

The notion of matching wine grapes to climate was not hatched by Coury or Lett, or their Davis faculty

predecessors, for it originated in the writings of Jules Guyot and Victor Pulliat in France in the 1800s. The idea

was researched in this country by noted American viticulturist, Albert J. Winkler, Professor of Viticulture in the

department at Davis in the mid-1900s. Together with his student and later colleague, Maynard Amerine, also a

professor at Davis, Winkler devised a heat summation system for grapes. The number of “degree days” of

sunshine an area received was quantified allowing growers to determine which grape was best suited to a

particular growing region. The degree days were determined by the length in days of the growing season and

the average daily temperature above 50ºF. The growing regions were classified from I (the coolest) to V (the

warmest). The scale was first published in 1944 and updated in 1963, and remains a standard directive for

grape growers in matching grape varieties to appropriate geographic areas.

From handwritten notes taken at University of California Davis, Lett clearly studied closely the writings of Victor

Pulliat (1827-1896) a French ampelographer, who took his inspiration from Dr. Jules Guyot (1807-1872).

Guyot was a French physician and agronomist who is best known for his work in viticulture. L’ institut

universitaire de la Vigne et de Vin (Institute Jules Guyot) at the University of Burgundy in Dijon is named in his

honor. He introduced the Guyot system of cane pruning of vines for trellises. Victor Pulliat, born in Chinobles

in the Beaujolais region of France, was a student of botany, and in particular, grape vines. In 1869, he started

the Regional Society for Vinegrowing and recommended grafting on resistant roots from America to renew

French vineyards devastated by phylloxera. He published Le Vignoble with Alphonse Mas (an apple tree

specialist) in three volumes between 1874 and 1879. This treatise contained descriptions of 228 grape

varieties.

Pulliat further wrote Mille Varieties de Vignes, Description and Synonymies (A Thousand Varieties of Vines,

Descriptions and Synonyms) in 1888, in which he described a grape maturity classification system used

worldwide by ampelographers. In the book, he quoted Guyot, who had contributed to his inspiration for this

system:

“C’est avec beaucoup de raison que le docteur Guyot a formulé ce principle en disant que ‘le

grand problème à résoudre pour nos différents crûs c’est de trouver la variété o de vigne la

mieux appropriée à un sol et à un climat donné.’”

“It is with good reason that Dr. Guyot formulated this principle by saying that, ‘The major

problem to be solved for our various regions is to find the variety of vine best suited to a given

soil and climate.’”

“Si ce problème a été résolu plusieurs de nos vignobles en renom il en est beaucoup encore

qui sont loin de obtenir leur maximum de rendement et de qualité faute de cultiver des

variétés de vignes bien appropriées aux conditions climatériques où elles doivent vivre.”

“If this problem has been solved for many of our renowned vineyards, there are many who

are still far from obtaining their maximum yield and quality due to lack of cultivation of vine

varieties well suited to the climatic conditions where they must live.”

Pulliat classified the principal Vitis vinifera grape varieties into five groups according to the order in which they

ripened in comparison to the Chasseles grape (Chasseles is the benchmark grape by which the dates of

maturity of the other grapes are compared). Lett applied the principles of ripening date classification outlined

by Pulliat in his choice of plantings for the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Mary Boyle (The Quarterly Review of

Wines, summer 1996) quotes Lett, “After my year of studying Burgundian varieties in France, I was sure the

marginal climate of the Willamette Valley was the perfect place to cultivate them in the United States.” Period I

grapes had the best chance of being successfully grown in the climate of the Willamette Valley and included

Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Muscat Ottonel, true Pinot Blanc and Chardonnay. Lett also added

Riesling, which although a Period II grape, developed flavors early and could be picked slightly underripe.

When Lett, at the tender age of 25, returned to the United States in the fall of 1964, he gathered 3,000 mostly certified grape cuttings

from University of California Davis and other sources. Armed with several thousand cuttings, Lett traveled to

the Willamette Valley and started a nursery just outside Corvallis in February of 1965 where he planted several cool-

climate Period I grape varieties including Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, and Pinot Noir ( Wädenswil -

1A and Tout Droit - UCD 18) and Period II Riesling. The vines were planted in rows to root while he

looked for an ideal vineyard site in the Willamette Valley.

The photo below shows a young David Lett before departing for Oregon in early February of 1965 with a trailer

full of vine cuttings packed in wooden wine boxes.

An entry from David Lett’s personal journal pictured below indicates Lett found a suitable site to lease for his

plantings in Corvallis on February 8, 1965. Lett borrowed a tractor to plow nursery rows for the Willamette

Valley’s first Pinot Noir vines on February 13, 1965. A photograph below shows the vineyard being plowed on

that date. In the journal, Lett reveals his concerns: “Slowly I am learning to be a farmer. I hope I don’t lose all

my cuttings while I’m waiting to get them in the ground and all my money while I am waiting for a job.”

Lett’s subsequent journal entry indicates the first planting of Vitis vinifera (including Pinot Noir) in the Willamette

Valley took place on February 22, 1965.

An additional journal entry by David Lett indicates that planting was complete on March 1, 1965.

A photograph shows David Lett christening the first planting in the Willamette Valley in the spring of 1965.

In the first half of 1965, the Courys were still living in California, visiting Oregon at intervals to look for vineyard

land. Lett’s journal indicates that on April 3, 1965, Lett planted some one-year-old cuttings for the Courys in his

Corvallis nursery, sent to Lett from California.

A photograph from June 1965 below shows Lett’s plantings in Corvallis. Note the mix of cast iron and

aluminum irrigation pipe and Lett’s hand tiller in the background.

David Lett subsequently located his original vines to his ideal vineyard site in the Red Hills of Dundee. Field

preparation and transplanting began in 1966 when David, along with his new spouse, Diana, founded The

Eyrie Vineyards. By their first vintage in 1970, the Letts had established 8 acres, approximately half of which

were Pinot Noir clones UCD 1A (Wädenswil) and UCD 18 (“Trout droit”). Pommard 5 would be added a few

years later.

After establishing some of his cuttings in Lett’s nursery vineyard in Corvallis in the spring of 1965, Coury found

a suitable location for his vineyard, winery and nursery in Forest Grove and bought the property in 1965. He

moved into a farmhouse on the property once owned by noted vintner Frank Reuter and planted his first

vineyard at Charles Coury Vineyards in 1966. There is no evidence to indicate that Coury planted his vines in

Forest Grove before 1966. The obituary of Coury’s spouse, Shirley, confirms that Coury’s first plantings in

Forest Grove date to 1966. The obituary reads, “With her husband, she established Charles Coury Vineyards

in 1966 on David’s Hill in Forest Grove, where they were among the earliest participants in the fledgling Oregon

wine industry.” (www.blues-star.com/news/obituaries/3638.html). Today, 3.9 acres of Pinot Noir survive

among Lett’s initial Dundee Hills plantings of 16 acres, and, along with Coury’s approximately 6 acres of

surviving Pinot Noir, are the oldest Pinot Noir plantings in the Willamette Valley.

Lett, who passed away in October 2008 at the age of 69, developed a gray-white beard in his later years and

was so revered by his peers, he was affectionately called “Papa Pinot.” He received considerably more

recognition than Coury, and deservedly so, since his Eyrie Pinot Noirs set the mark and won international

recognition for the fledgling Oregon wine industry.

At a Gault-Millau-sponsored tasting held in Paris in 1979, “Olympics of Wines of the World,” a number of non-

French wines placed near the top. The following year, Robert Drouhin gathered an international distinguished

panel of judges who blind-tasted the wines against burgundies from the cellars of Domaine Drouhin in Beaune.

A 1959 Domaine Drouhin Chambolle-Musigny came in first, but David Lett’s 1975 Eyrie Vineyards South Block

Reserve Pinot Noir took second, ahead of Drouhin’s Chambertin. Bill Hatcher, formerly manager at Domaine

Drouhin and now a partner in A to Z Wineworks in Oregon), called the 1975 Eyrie Pinot Noir, “The communion

wine of the Oregon Wine Industry.”

Lett followed the European model of winemaking, relying on low yields, small lot fermentations and French oak

barrel-aging to produce exceptional wines. He remained faithful to a consistent theme of classically styled Pinot

Noir that aged incredibly well. He was innovative (rather than iconoclastic as some proclaimed), practicing leaf

pulling to limit yields and vertical trellising, viticulture techniques now widely used in cool climates. He was a

firm believer in organic farming, said to be heavily influenced by Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring.

Published in 1962, the book decried the use of pesticides. Until the 1980s, Lett performed all the important

vineyard and cellar work himself.

Rene Chazottes, a master sommelier who first drank wine with Lett at Nick’s Cafe in McMinnville over twenty-five

years ago and came to know him well during several visits during the ensuing years, told me he was

impressed by Lett’s ambition and focus. As Lett walked his vineyard, he could point out among the many vines

which were the most productive and which gave birth to the top quality grapes.

Lett continued to hone his craft through a career spanning almost 40 commercial vintages, holding the

distinction at the time of his passing of producing a single vineyard Pinot Noir longer than any other winemaker

in the United States. In addition, he had the honor of producing the first New World Pinot Gris in 1970, a

variety that was to become Oregon’s signature white wine. David’s son, Jason, assumed the winemaking and

vineyard management reins in 2005 and the winery has not missed a beat (father and son pictured below).

Coury, although extremely bright, never achieved the winemaking success of Lett. Dick Erath, when asked

about Coury, is quoted in the Oregon Wine News interview (March 2011) as saying, “Unfortunately, he didn’t

have the follow through...He just couldn’t get from A to Z.” Andrew Barr (Pinot Noir 1992) quotes Lett as

saying, “Coury was a wonderful theoretician,” and therein may have been his downfall. Coury attempted to

follow the California production model of the time, employing high yields and minimizing the importance of

barrel aging. His wines, as a result, never achieved critical success and he was unable to develop a following.

Coury finally left the Willamette Valley in 1978, ceding his winery to Dave Teppola who founded Laurel Ridge

Winery on the site, later to become the David Hill Vineyard & Winery under the current proprietorship of Milan

and Jean Stoyanov. After the sale of his winery, Coury became a pioneer in the microbrewing industry in

Portland, but that venture was unsuccessful as well, and he returned to California where he passed away

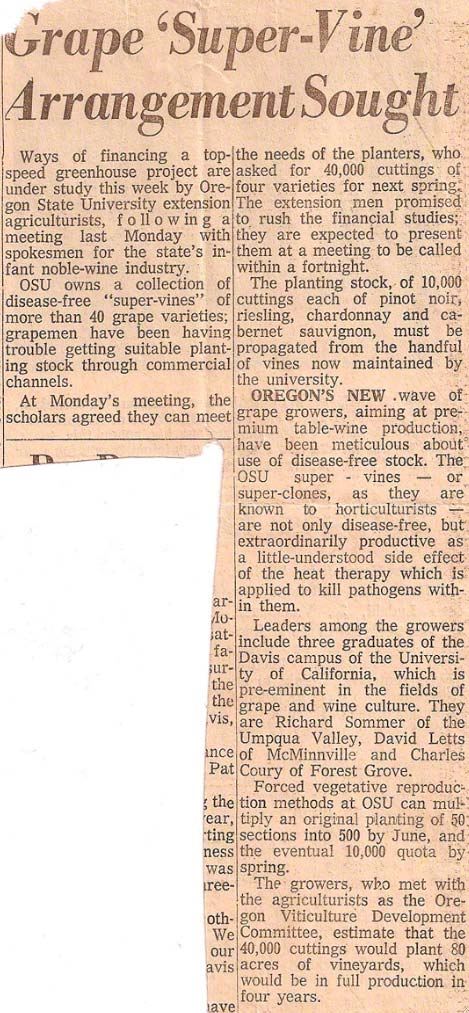

relatively anonymously in 2004 from lung cancer at the age of 73. Coury’s legacy will include working with

other early vintners to establish a viticultural research center at Oregon State University, taking part in the

formulation of ideas that led to Oregon’s labeling regulations and, along with Lett and Sommer, establishing

quarantines on vine material (see Oregon newspaper article that references their work below). He also

introduced the Pommard selection to Oregon in the early 1970s as part of a joint nursery venture with Dick

Erath, as well as another Pinot Noir selection rumored to have come from Germany and which in Oregon is still

known as the Coury clone.

In summary, the controversy of who planted Pinot Noir first in modern times in Oregon can be laid to rest.

Richard Sommer, who put Pinot Noir into the ground in the Umpqua Valley in 1961, was the first. He was also

the first vintner in the modern Oregon wine industry era to release a varietally labeled Oregon Pinot Noir

(1967). David Lett holds the distinction of being the second to plant Pinot Noir in Oregon and the first to plant

Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley. He also was the first to plant Pinot Gris in the Willamette Valley. Charles

Coury was the third vintner to cultivate Pinot Noir in Oregon and the second to plant Pinot Noir in the

Willamette Valley. Lett and Coury established their first estate vineyards in 1966, Coury in Forest Grove and

Lett in the Red Hills of Dundee.

Forest Grove’s claim, “Where Oregon Pinot was born,” based on the evidence presented here, is unfounded,

misleading, and should be retracted.

Adam Campbell, who is the owner and winemaker of esteemed Elk Cove Vineyards in Gaston, near Forest

Grove, said in the Forest Grove News Times (February 16, 2011), “Boasting about where Oregon Pinot Noir

was born is really antithetical to the culture of how Oregon wineries sell our wine and educate people about the

area. I think the slogan is divisive, probably not true and really not the most important thing about not only the

city of Forest Grove but the winegrowing community that surrounds the city.”

Jason Lett is in the process of creating an archival-rich website that will provide historians a valuable source of

accurate information about David Lett and The Eyrie Vineyards.

A sampling of releases from The Eyrie Vineyards, 2002 to 2009 vintages, follows.