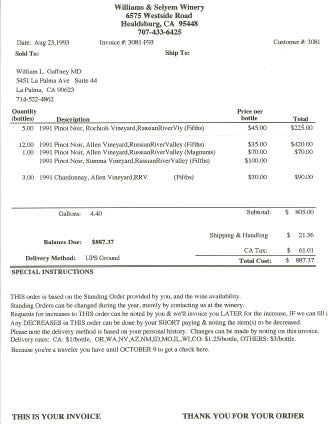

Russian River Valley-Beaune in USA

Located sixty miles north of downtown San Francisco, the Russian River Valley is a

box-shaped region in northern Sonoma County just fifteen miles on any side. One

of thirteen appellations in Sonoma County, the four corners of the Russian River

Valley consist of the towns of Healdsburg and Guerneville in the north and Sebastopol

and Santa Rosa in the south. The Russian River Valley comprises 126,600

acres of rolling hills, dense red wood forests and apple orchards with 15,000 acres

planted to vineyards (depicted in green on the map below).

The Russian River Valley and River are named for Russian explorers who settled at Fort Ross, just north

of Jenner where the Russian River empties into the Pacific Ocean. According to Steve Heimoff, writing

in A Wine Journey Along the Russian River, the Russians landed on the Sonoma Coast at a site populated

by a Pomo Indian colony that the natives had named Metini. The Russians worked out a deal with the

Indians to settle at Metini and they named their new village Rossiya, after the name historically given

to their Russian homeland. It was years later before it became known as Fort Ross. The Pomo Indians

were the original inhabitants of the Sonoma Coast and the Russian River Valley and had named the

Russian River Shabakai or “long snake,” for its many twists and turns. The Russians adopted their own

name for the River, Slavianka or “pretty Russian girl.” By 1867, the Russians had left North America

entirely, leaving behind the anglicized names Russian River Valley and Russian River as their legacy.

The defining feature of the Russian River Valley is a single three-letter word: fog. Fog from the Pacific

Ocean is the most important single influence on viticulture here and it defines the boundaries of the

Russian River Valley appellation which was established in 1983. The fog enters the Valley during the

growing season from the southwest through the Petaluma Wind Gap between Pt Reyes and Bodega

Bay, with a smaller incursion traveling inward along the Russian River from its origins at Jenner on the

Sonoma Coast. Plenty of daytime warmth (the Russian River Valley is a Region III on the University of

California Davis scale) gives way to cool nights and mornings caused by the fog that pours in through

the Gap. The result is slowed ripening and extended hang time for the grapes. The winegrowers here

like to say that they turn fog into Pinot Noir.

There are many varietals that thrive in the diverse microclimates of the Russian River Valley. It was the

so-called “field blends” of varietals such as Grenache, Mourvèdre, Carignane, Petite Sirah, Syrah and

Alicante Bouschet along with Zinfandel that the Italian Americans grew so successfully and popularized

here. Some of these Italian-American immigrants’ families, such as Seghesio, Rochioli, Pedroncelli,

and Pellegrini, are still making wine in the Russian River Valley. With time, the region has become the

chosen one for growing the Burgundian varietals, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

The Russian River is 105 miles in length, beginning its journey in the coastal mountains in the north

near the town of Willits in Mendocino County, and winding south through the Alexander Valley before

reaching the Russian River Valley. Just below the town of Healdsburg, the River takes a turn to head

west toward the Pacific Ocean. The surrounding area here is the so-called Middle Reach of the Valley,

the sweet spot and birthplace of modern Pinot Noir viticulture in the Valley.

The first to plant Pinot Noir along Westside Road

in the Middle Reach was Steve and Helen

Bacigalupi in 1964 (Steve Heimoff notes that

Korbel has planted Pinot Noir as far back as the

1950s, but this was a few miles west where

Westside Road ends at River Road near Guerneville).

In 1968, shortly after his father passed

away, Joe Rochioli, Jr. (pictured right) in deference

to his father’s wishes planted Pinot Noir on

Westside Road along the banks of the Russian

River. This became the now infamous East

Block of Pinot Noir. West Block followed a year

later. In 1973, Davis Bynum, a San Francisco

Chronicle reporter, built the first winery on

Westside Road and he produced Pinot Noir from

Joe Rochioli Jr.’s first crop. The

1973 Davis Bynum Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir was the first Russian

River Valley vineyard-designated wine. The following year, Gary Farrell, who had majored in

political science at Sonoma State University, decided to become a winemaker and took a job at Davis Bynum. In 1982, Gary Farrell started his own label, Gary Farrell Wines, crafting Pinot Noir from

Rochioli grapes vinified at Davis Bynum. He continued as winemaker for Davis Bynum until 2000. Also

in 1982, Joe Rochioli Jr. and his son Tom started the Rochioli label. The first wines were made by

Farrell at Davis Bynum. By 1985, Tom had quit his job in the banking business and joined his father as

the winemaker. Early on Gary Farrell continued as a consultant and assisted in the planning and

construction of the Rochioli winery.

Gary Farrell would often hand-deliver his wines to customers in the Valley, one of whom was Ed

Selyem, who was the wine buyer for Speer’s Market in Forestville. In a

sfgate.com article dated

8/22/06 written by Linda Murphy, Gary Farrell was reported as saying, “Their (Ed Selyem and Burt

Williams) entry into the business caught me by surprise. Ed would ask me about the Rochioli vineyards,

about winemaking, and I gave him the recipe. It never occurred to me what he was up to until

Joe Rochioli told me that he’d sold grapes to Williams Selyem.”

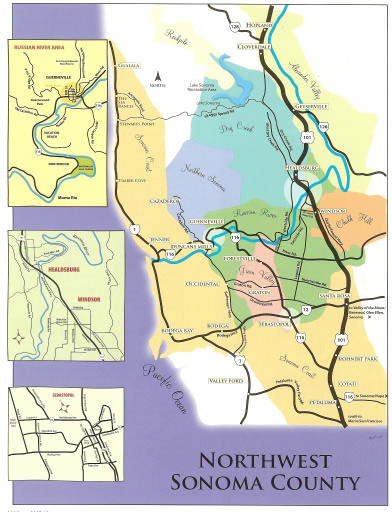

The now legendary Williams Selyem Winery

was the original Russian River Valley garage

winery. Burt Williams hailed from Sebastopol,

worked as a proofreader for the San Francisco

Newspaper Agency (Chronicle and Examiner), and made wine at home. Ed

Selyem was a wine buyer and accountant for a small grocery store and crafted beer and fruit wine in his

garage in Forestville. Together they began

making wine from Sonoma Zinfandel grapes for

their own use in 1979. Their first commercial

winery was based in a rented garage on River

Road in Fulton beginning in 1984 (photo right

shows a recent photo of the garage).

The original name of their winery was Hacienda del Rio, a name Ed used on his first home-crafted

wines. The photo below left shows the 1980 Hacienda del Rio label. This wine was produced in Ed's

Forestville garage by Ed and Burt for friends and family and was not released commercially. The first

three commercial Pinot Noirs, 1981-1983, were made at Russian River Vineyards in Forestville, and bottled

under the Hacienda del Rio name. The wines were an instant success and Burgundy lovers began

to talk about the Williams Selyem Pinot Noir in revered tones. The Hacienda Del Rio label (below

right) looked exactly like the current Williams Selyem label, using the same letterpress lettering,

color and paper. A complaint from Hacienda Winery prompted the partners to drop the original name

and substitute their own beginning with the 1984 vintage.

Williams was a burly vintner who had an uncanny and self-taught sense of how Pinot Noir should be

vinified. He never set foot in Burgundy. Production methods were old-fashioned to say the least,

prompted by the lack of capital. In the early years, Burt continued his job in San Francisco as did Ed at

Speer’s Market and they took vacations at crush time. They began with little money, never borrowed,

and grew 25% every year by starting small and plowing all of their income back into the business.

Wives Gayle Selyem and Jan Williams were also partners in the winery which early on hired no outside

help. It was a perfect business partnership as Burt was driven to make world-class wine and Ed

was determined to create a successful business from local agriculture. Burt preferred colorful sport

shirts with suspenders, Ed opted for t-shirts and boots. Both lived simply and shunned publicity.

There was never a sign at the garage announcing the winery’s location and there was no tasting room.

There were no great secrets to their success. They carefully chose their grape sources and did all of

the work in the winery themselves. Over time North American vintners have come to realize that Pinot

Noir requires delicate handling and constant vigilance in the winery, two things Ed and Burt practiced

from the start. Their winemaking methods were Old World (Burgundian if you will) primarily out of

necessity because they had little money to fund their operation. Their techniques were very labor intensive

and inefficient, but the result justified the effort. The Williams Selyem Pinot Noirs were

brimming with varietal character and although light in color, they had superb aromatic and flavor intensity.

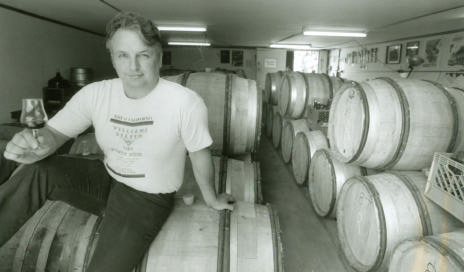

Denise Selyem, Ed’s daughter, recently was kind enough to share two photographs of Ed working at

the original winery in Fulton. The picture on top shows Ed outside the garage with the small, double walled,

stainless steel, recycled, open-top dairy tanks salvaged from a Windsor dairy farm in which

fermentations were carried out. The method of Pinot Noir production employed by Burt and Ed is now

currently practiced at least in some form by most California vintners of the Pinot Noir grape. Both Burt

and Ed constantly checked on the grapes in the vineyard. The grapes were picked ripe, put into

wooden crates and transported by pickup truck to the winery (see old photo on page 6) where they

were hand-sorted destemmed. Fermentations were long and cool. They got into the tanks and did some punch downs, but there was no crushing. The must was lightly pressed using a hand-operated

basket press dating from 1906. The wine was gravity-racked and the last gallons of juice were lifted

out of the tanks in buckets. The wine never saw a pump, a fining agent, or filtration. Aging was

carried out in mostly new French oak 225-liter barrels from Troncais made by Francois Freres. The

barrels were never used more than twice. The wine was hand-bottled, labeled and foiled.

The other photo on page 5 shows Ed inside one of the large shipping cargo containers which were

rigged to store barrels. The containers once held New Zealand lamb carcasses. Ed developed the

concept of a mailing list to distribute their wine long before mailing lists became the accepted way of

allocating scarce wine in California. Early on the wine was sold mainly to other winemakers and retailers

with good palates to whom the wine was often hand delivered.

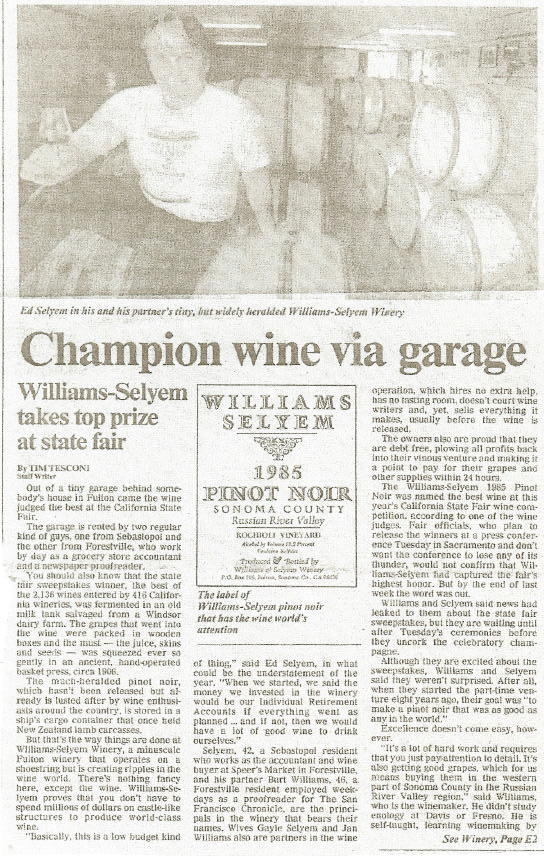

The more wine Williams Selyem made, the more favorable the press that followed, causing a snowball

effect in demand. The 1985 Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir

became the most seminal wine in the history of California Pinot Noir. This wine won the Sweepstakes at

the California State Fair Wine Competition, voted the best of the 2,136 wines entered by 416 California

wineries in 1987. 295 cases of the wine were produced and it sold for $16 a bottle! A copy of the original

newspaper article which appeared in the Santa Rosa Press Democrat is on page 7 which includes

the photo of Ed I obtained from Denise on page 5.

One of the keys to the success of Williams Selyem was that they were able to successfully contract with

the very best growers in the Russian River Valley. It was a simpler time and the growers were friendly

and unassuming folks that were easy to work with. All of Williams Selyem contracts were on a handshake

basis. Williams Selyem never did own any vineyards. Their now famous vineyard sources for

Pinot Noir included Rochioli Vineyard, Allen Vineyard, Cohn Vineyard, and Olivet Lane Vineyard in

the Russian River Valley, Summa Vineyard, Coastlands Vineyard, and Hirsch Vineyard on the Sonoma

Coast, and Ferrington Vineyard in Anderson Valley. In 1989, Howard Allen, owner of Allen Vineyard

which was located across Westside Road from Rochioli, built them a winery on his ranch which they

leased allowing them to move out of their rented garage in Fulton.

Williams Selyem Pinot Noir wine became so popular that a waiting list was developed for those

begging to get on the mailing list. Eventually 85% of their wine was sold directly to individuals on the

carefully guarded mailing list. Ed managed the list masterfully and enjoyed being in contact with,

visiting with, and learning from his devoted customers.

Williams Selyem produced credible Zinfandels (Ed and Burt thought initially that Zinfandel would be

their most successful wine) and Chardonnays, but it was the Pinot Noirs that drew most of the attention.

The Pinot Noirs were amazingly fruity and complex when young and seemed to age better than most

Pinot Noirs in California. The Pinot Noirs peaked around 6-7 years after release, but it was very difficult

to avoid drinking them young. The unlikely owners and the scarcity of their wine created a mystique,

but it was the wine’s quality and consistency that was the attraction. I was one of the fortunate

ones to be included on the mailing list beginning in 1991 (customer #3081) and the greatest California

Pinot Noir I have ever had was the

1992 Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Valley

Pinot Noir. Alas, I learned recently that you can never go back. I purchased a bottle of this wine on

the secondary market as well as a bottle of the 1990 vintage. Now 15 and 17 years old respectively,

the wines showed brief flashes of their former brilliance upon opening, but quickly faded to ordinary

drink ability. A copy of my 1991 vintage offering from Williams Selyem is on page 9.

Wine writers of the 1990s spoke about Williams Selyem with superlatives

previously reserved for Burgundy such as, “Well-balanced, ripe

and juicy flavors, rich and supple texture, voluptuous and intensely

flavored, delicacy and finesse with profound flavor.” Dan Berger

raved, “Best Pinot Noir in America and a rival to the best in the world.”

Matt Kramer anointed Williams Selyem, “The Best Pinot Noir in California.”

Anthony Dias Blue chimed in, “Williams Selyem Pinot Noir shines

above the rest.” The customers were among the most devoted of any

winery I have experienced then and now. Chris Crevasse of Tennessee

wrote, “We are a little concerned about my brother-in-law, who had

never tried world-class wine until we shared a bottle of your 1991

Olivet Lane with him. Now he’s lost interest in work and has moved the

La-Z-Boy downstairs in the wine cellar. He claims he just wants to watch

but it’s hard to say what needs watching down there. We’re all hopeful that he’s just displaying the

initial zeal of a new convert, and that he will return to a more or less normal life when he gets accustomed

to venerating your wine.”

Win Wilson and Jack Daniels, the Napa Valley importers of Domaine de la Romanee-Conti came calling

to Williams Selyem in 1992. They wanted to compare wines. 22 wines and 5 hours later, no conclusions

were publicly reported, but the reason to do such a comparative tasting indicated the cache that

Williams Selyem had gained with the wine industry.

The popularity of their wines took their toil over the years on Ed and Burt. Managing the mailing list

and the hoards of wine enthusiasts trying to get on the list was a daunting task. Two of the seven fulltime

employees in the mid 1990s were designated as “keepers of the list.” Frank Prial, writing in The

New York Times (March 19, 1997), related a story about Ed Bradley, a correspondent on CBS’s “60 Minutes,”

and a wine enthusiast who wanted to get on the mailing list. Burt Williams said, “He told us that

if we didn’t put him on the list, he’d get Andy Rooney to do a commentary on people who keep lists.

Well, we couldn’t have that. So we put him on.” The partnership slowly developed some rife and Williams

Selyem was put on the market in 1997. It was eventually sold to John Dyson in 1998 for $9.5 million.

The official word was that Ed developed serious back problems from lifting wine cases over the

years, but the reasons had to be more complicated, yet were never divulged. The last vintage that Ed

and Burt vinified at Williams Selyem was 1997, with Burt consulting on the 1998 vintage. At the time the

winery was sold, there were 10,000 customers on the mailing list.

John Dyson, a wealthy New York politician, was a former New York state agriculture commissioner and

a former deputy mayor under Mayor Rudy Giuliani. He owns Millbrook Vineyards in upstate New York

and Villa Pillo Estate in Tuscany as well as Mistral and Vista Verde Vineyards on the central California

coast. He essentially paid a lot of money for the Williams Selyem name since Williams Selyem owned no vineyards or winery. In addition, he lost some hand-shake agreements such as the grapes from

Olivet Lane, Summa and Rochioli’s West Block. Several of the vineyard sources were retained.

Ed and Burt almost closed the winery for good before agreeing to sell Williams Selyem to Dyson, a

long time member of the mailing list. Upon purchasing the winery, Dyson hired the relatively unknown

Bob Cabral as his winemaker. Cabral (customer number 576 on the Williams Selyem list) was the son

of grape farmers who earned a degree in enology at Fresno State. He learned his trade at De Loach

Vineyards, Knude, Alderbrook and Hartford Court. Since assuming winemaking responsibilities,

Cabral has tried to follow Williams’ winemaking methods. After an inauspicious start (it is always difficult

to follow a legend), he is producing Pinot Noirs that are still eagerly sought after by the now 15,000

customers on the mailing list. The wines are a touch higher in alcohol, deeper in color, and offer more

fruit-driven flavors. As the winery now celebrates its 25th Anniversary with the release of the 2005 vintage,

the wines are carrying the flag with respectability and the single-vineyard designates continue to

be the stars.

Burt now splits his time between his ranch in the Anderson Valley and his fishing boat in Santa Barbara.

He grows Pinot Noir on his Morning Dew Vineyard and sells the grapes to his daughter at Brogan

Cellars and to Woodenhead and Whitcraft. When I asked him the inevitable question about making

his own Pinot Noir again after the non-compete agreement ends next year, he was noncommittal, but

said, “If I do decide to do it, I will devote all my energies seriously to the task. I will make small

amounts and it will cost a lot of money.” Ed has been spending his summers in Alaska and winters in

both California and Hawaii. His daughter, Denise Selyem and her husband Kirk Hubbard, craft Pinot

Noirs under the WesMar label, working in a small winery in Sebastopol reminiscent in size of the

original garage that Ed and Burt started with. Over the years, Williams Selyem became a training

ground for many other winemakers and a number of labels carry on the legacy including Papapapietro

Perry, Woodenhead, george, Cobb, and Anthill Cellars.